25/06/2019

Future=machine?!

Machine translation, artificial intelligence and machine learning are the words on everyone’s lips. We discussed the topic with our in-house expert in machine translation and post-editing. This produced exciting insights into best practices, challenges and opportunities for customers, freelancers and project managers …

What do companies that opt for machine translation (in short: MT) need to know? How do they identify a good provider and does it really always result in cost and time savings? What can translators do to benefit from the new technology? Emela, an intern on the BOGY trainee programme, and marketing manager Carolin Bauer asked MT expert Nikolina Cabraja these and many other questions. She has been with oneword for 2.5 years and supports companies in introducing and implementing translation projects using machine translation and post-editing (PE).

From the oneQuestion series: oneAnswer

Machine translation vs. human translation

Nikolina, first of all, thank you so much for your time. Why don’t you briefly explain to our readers what the general advantages of machine translation are and why companies should use this technology?

In general, companies that come to us know that machine translation can cut costs and greatly minimise the time required compared to human translation. While a translator can translate about 1500 words a day, a machine can handle this volume mercilessly within a few seconds – to put it bluntly.

Are all types of text suitable for machine translation?

In principle, anything is possible, but it works particularly well with standardised, technical texts. It becomes more difficult with marketing texts: anything that uses figurative language, contains special idioms or puns, or is written in a very flowery style is difficult for the machine. And the results are now much more satisfactory than just a few years ago. Technology is making really great strides in this area.

Furthermore, it simply depends on how critical or how risky the texts are and what they are used for. Will the content be read by an in-house or external target group? Is the text going to be used for a long time or only in the short term to put a subject into context, for example?

Machine translation: the numbers game – significantly more volume in less time, using high-quality post-editing. Sounds tempting. Is it?

Cutting costs with machine translation

From what I hear, categorising texts, for example by target group, degree of risk, content and purpose of the translation, could help to better estimate the cost benefit. Is that right?

Definitely. We are also talking about risk management here. The more independent the variables, the more conclusive the estimate. Prioritisation is also important. For example, generally speaking, a short-lived translation, such as a current press release, can be classified as “appropriate for MT”. However, the target group is outside of the company and comparatively large. High quality standards and rules for post-processing must therefore also be established. The same applies, for example, when an operating manual for a very specific circular saw is translated. In this scenario, the target group can be as small and specific as you like, but since there is a danger to life, there should be knock-out criteria in place.

These should be established as part of a feasibility analysis and should allow us to estimate, based on the classification of the text, which combination of human or machine translation, full or light post-editing and possibly even additional revision and technical review stages is suitable. Then, companies often discover for themselves that, at some point, clustering ushers in the “break-even point” text category. Of course, we are not talking about profit and loss here, but there comes a point when additional costly checks almost cancel out the costs saved by using MT in the first place, and companies should ask themselves the question: Am I saving time or money from this point on?

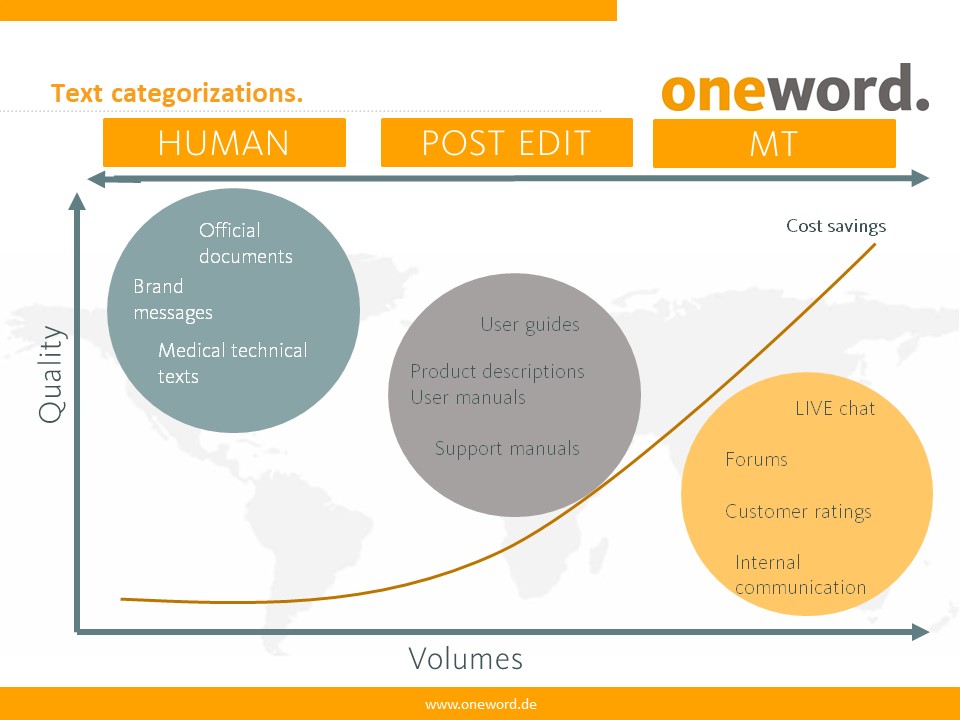

Categorising the existing documents can be an initial decision aid to find out the best possible saving potential for each text type. (source: oneword)

Commissioning machine translation: What do I have to watch out for?

Who decides whether a translation should be produced by a human or by a machine? The language service provider or the company?

This is always the customer’s decision, but we provide comprehensive advice, carry out a feasibility analysis and support them in implementing their decision during and after the decision-making process. Together, as part of MT, we can set up a process that aims for a high-quality end product, even if the source text is complex and demanding.

The classification mentioned above generally helps customers to make their own decision and also to assess in advance which service provider will provide in-depth advice in this area and look at the customer’s texts individually and differentiate sufficiently between them.

This leads us directly to the next question: In as early as 2016, the Common Sense Advisory said that 80 percent of LSPs offer MT. This raises the question of whether there are any quality attributes or indications that help to assess the quality and range of services offered by individual service providers. Do you have a tip for the customer?

The initial consultation between the customer and service provider already speaks volumes, in my opinion. It is therefore important that the service provider takes enough time to find out what the customer’s requirements and needs are, what type of texts, volumes and quality demands they have, whether they require full or light post-editing, what systems are suitable for this and how the machine should be trained in the long term. As a customer, I then quickly identify whether the agency knows the ropes and can also provide me with a tailor-made range of services.

The issue of data protection should also be discussed. Does the service provider handle my data sensitively, or are the results and texts stored somewhere cloud-based or reused in another context? How much will I be involved in training the engine? What are the feedback processes like? Where should the machine translation take place and what do I, as a customer, have to purchase for my own office? As well as noting a company’s professionalism and skills when having these conversations, I also notice a provider’s skills if they have the Quality seal of the post-editing standard DIN ISO 18587. A few service providers have this certification, which also helps to identify how far the providers have already come in terms of their range of MT services. oneword is one of the fast movers and intends to be certified before the end of 2019.

Speaking of training: Is it even possible to integrate style guides and terminology into the translation process?

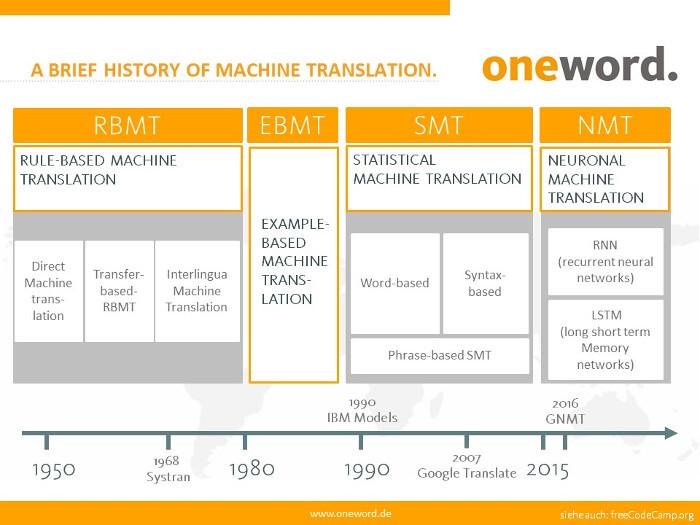

There are different types of MT: statistical, rule-based and neural. In principle, terminology can be incorporated into all of them.

You have to differentiate when referring to style guides. Concrete rules such as “Formulate in noun-based sentences only” or “Only use short sentences” can be easily integrated into rule-based MT. However, even when using human translation, it’s sometimes difficult to define the desired style in a style guide to the extent that third parties, such as the translator or reviser, always adhere to it and implement it exactly. That’s because style is subjective. So the less concrete a rule is, the more difficult it is for the machine to implement it. This means: in MT, style guides are particularly important for the post-editor. Throughout the entire post-editing process, they pay particular attention to adequately implementing complex stylistic requirements, such as rhymes, idioms or puns. That’s exactly why it’s so important that MT only takes place without PE in exceptional circumstances.

Machine translation challenges

What are other general stumbling blocks for the machine?

As a fundamental principle, source texts should not contain any spelling mistakes. For example, the machine cannot automatically establish that the correct spelling of the word “hitnerlegt” is “hinterlegt“, and translate accordingly. As a completely unknown word, it’s treated as a proper noun and remains untranslated.

A source text that already contains individual terms from other languages is also problematic. In German, for example, many Anglicisms are used: the English term “backend” is used as a synonym for the back room of an IT system. Yet it’s also used as a participle for the German verb “backen” (to bake). Therefore, when machine-translated into English as the target language, the term quickly turns into “baking” and could cause some confusion in the wrong context.

As a general principle, it’s important to continuously feed large, clean data into the machine and provide a lot of training material to train the engine and to correct it time and time again. This is also how a style is acquired. The machine can only learn if it has consistent information.

Let’s look even more closely at the translator’s side of the MT process. Traditional translators often feel left out when it comes to training the engine. Do you have any tips for training and how translators can be better integrated into the process? What training strategies are there?

We involve our translators and post-editors using a comprehensive feedback form that asks for an evaluation of various aspects of the translation so that we can optimise the machine or process afterwards. Our project managers are also trained translators and linguists. It’s essential that linguists also participate in training the machine, not just the customer’s technical expert.

There are also companies that have their machine-translated texts rated by the target group via surveys and Likert scales. The question here is always: What is the aim? It’s clear that you should ask if there are obvious mistakes, whether the wording is well-phrased and uses the correct grammar. But what if you don’t like the style? Language and style are always very subjective. That’s why I have to consider which and how many people I let participate in the training and what should ultimately satisfy whom.

Is a machine as good as a translator? If so, do you still need humans in the translation process?

The machine is getting better and better, there’s no question about that. Especially since neural systems like DeepL have conquered the market, significant progress has been made in machine translation. However, we also know from other sectors, such as the automotive industry, that you should never rely solely on technology or machines in important processes. Even if you have the latest navigation system in your car, you still have to pay attention to traffic signs, etc. It’s a similar thing with machine translation: not everything that comes out of the machine is correct. As mentioned before, language is not just a construct of words. There are other factors that make human translators irreplaceable. A machine does not detect ambiguity, cannot read between the lines, does not understand allusions, has no intercultural skills, etc.

What’s more, the machines still translate sentence by sentence without using the whole text as context. This leads to many inconsistencies and sometimes completely inappropriate translations. Of course, depending on the importance, target group and use of the translation, it’s possible not to post-edit the machine output. This is especially the case if the translation is purely informational, for example to understand the content of an e-mail within a company. However, for the end result to be a high-quality product that is indistinguishable from a human translation, machine translation currently still cannot be used without the “human” element.

Post-editing under the magnifying glass

These arguments will reassure many translators. What exactly does a post-editor do?

In the first instance in post-editing, it’s important that the customer decides in advance what quality requirements they have for the translation. If the machine translation is to resemble a human translation, full post-editing is definitely required. The post-editor checks each sentence in the machine translation, compares it with the source text and, if necessary, adjusts the target text. The post-editor makes sure that the machine hasn’t left anything out or added anything, that everything has been translated consistently and that the machine has translated everything correctly. However, if the machine translation is only going to be used for internal purposes and to obtain information without being published, light post-editing may be sufficient. Minor errors are allowed – adjectives are not adjusted and singular/plural mistakes are left, for example – since the translation can still be understood even with these grammatical errors and the post-editor should spend as little time as possible on the job. Another important task of the post-editor is to check terminology. Terminology can be included in the project, but, depending on the machine translation system, there is no guarantee that it will be adopted. Last but not least, the post-editor gives feedback on the types of errors that frequently occurred. This feedback helps to train the machine and also allows the source texts to be improved and made more “machine readable”, which, in turn, optimises the output of the machine.

At the last tekom in Vienna, some translators were a bit panicky about the technological developments. Have you got any advice for them?

On the one hand, I can very much appreciate why. On the other, 30 years ago there were no CAT tools. This means: we have always been exposed to technological change in our industry.

Translators should therefore always specialise. Post-editing is a highly sought-after additional qualification, which is linked to the demand and importance of machine translation and will therefore be even more prevalent in the future.

MT should therefore not be seen as a danger, but as an opportunity. Not every translator is a born post-editor, but training and further education can help them to make friends with it.

There are also other developments happening: while some customers rely primarily on MT, others are specifically interested in transcreation or SEO translation: texts that require incredible linguistic skill, cultural sensitivity and eloquence. More than ever before, the human translator is needed here, not the machine.

Development of MT over the past 70 years (source: oneword)

The post-editor’s capabilities

Are there any specific skills that a post-editor absolutely needs?

The motto is always: change as little as possible, but as much as necessary. If the post-editor turns everything on its head, the time and cost advantages over a human translation are lost, meaning that using machine translation is no longer worthwhile for the customer. Therefore, a post-editor has to be able to make quick decisions: can a sentence be left as the machine translated it, are changes necessary or does the sentence need to be completely re-translated? Any translator offering post-editing services should also be familiar with the different systems, as this knowledge is crucial later on when evaluating the machine translation output. Not every system makes the same mistakes. One system can have pitfalls that other systems do not have or hardly have at all. As already mentioned, every translator should see post-editing as an opportunity and not as a danger, and find out for themselves whether they want to specialise in it or not.

Thanks for the interview, Nikolina, and see you soon!

8 good reasons to choose oneword.

Learn more about what we do and what sets us apart from traditional translation agencies.

We explain 8 good reasons and more to choose oneword for a successful partnership.