23/01/2024

Translation-oriented writing for work with CAT tools

“Garbage in, garbage out?” was the title of the presentation that our Head of Quality Management, Eva-Maria Tillmann, gave last November at tekom (tcworld). Now the findings she presented are available to read and learn from. In the following article, she explains how working with computer-aided translation (CAT) tools is related to translation-oriented writing. And she explains small ways in which optimisations can help to reduce translation errors, lost time, additional costs and unnecessary queries.

Translation-oriented writing

A brief introduction: Translation-oriented writing means that the translation process is taken into account when the source language content is created. It does not matter whether the translation is done by a human or a machine. Source language content covers not only text, but information in any form (DIN ISO 20539:2020) – including audio and video.

Translation-oriented writing pursues clearly defined goals:

- reduction in translation errors due to incorrect, incomplete or inconsistent source language content

- reduction in unnecessary queries due to misleading or unclear source language content or a lack of context and reference information

- reduction in additional work and lost time due to file preparation (typing out texts, pre-editing, formatting corrections, etc.), file post-processing (layout optimisation), query management and subsequent correction processes

- reduction in additional costs

The current regulations for technical source language texts, e.g. the documentation standard IEC/IEEE 82079-1:2019, aim to ensure the error-free, safe and efficient use of products and machines. They therefore also deal with the completeness of sentences, the compactness of information, consistency, comprehensibility, clarity, logic, terminology and many other topics that are also relevant to translation-oriented writing. So why do we need more recommendations? If the source language content is comprehensible to users, is it not automatically comprehensible to translators as well?

Adherence to the specifications, e.g. from the documentation standard, does help the translator to correctly understand the content. However, the recommendations and specifications in the regulations for source texts do not take into account the translation process and the fact that professional translation involves the use of translation technology.

Translation technology

The term translation technology refers to all tools used in the translation process – i.e. for human translation, revision, post-editing of machine pre-translation and technical review. These tools include, for example, translation management systems, translation memories, terminology databases, machine translation systems, content management systems, DTP software, evaluation software, quality control software, tools for revision or review, localisation systems, language recognition software, keyword tools and many more. (See also ISO 17100, Annex E.)

Translation is not undertaken in the source file, but in CAT tools in which translation memories, terminology databases etc. are integrated. The source language content is imported into the CAT tool, where it is translated, and once the translation is complete it is replaced with the target language content in the original file, without the translator even having to open the source file. This saves translators from having to purchase a lot of additional software (e.g. InDesign).

Translation memories and their segmentation rules as well as terminology databases and terminology recognition are particularly relevant for translation-oriented writing.

Translation memories and segmentation

A translation memory (TM) is the translator’s digital memory and stores so-called segment pairs of source and target language content for one language direction (e.g. German-English) at a time. The translator can search through these segment pairs and reuse them in future translations.

The segmentation rules in the TM determine which text units from a source file form a segment in the CAT tool and where a new segment begins. A segment can consist of a sentence, a heading or just one single letter and always ends with a stop mark. By default, this means a full stop (.), exclamation mark (!), question mark (?), colon (:), hard return (¶) or the end of a table cell.

Terminology databases and terminology recognition

Terminology databases contain the terminology of a specific company or subject area, i.e. technical terms with the corresponding designations in all relevant target languages. Maintaining the terminology and using it in the translation ensures terminology consistency across all translations.

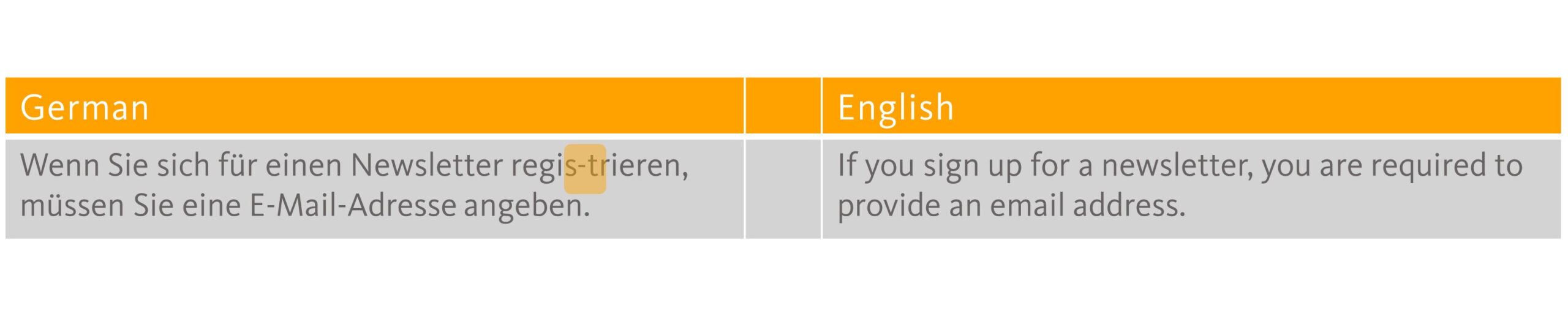

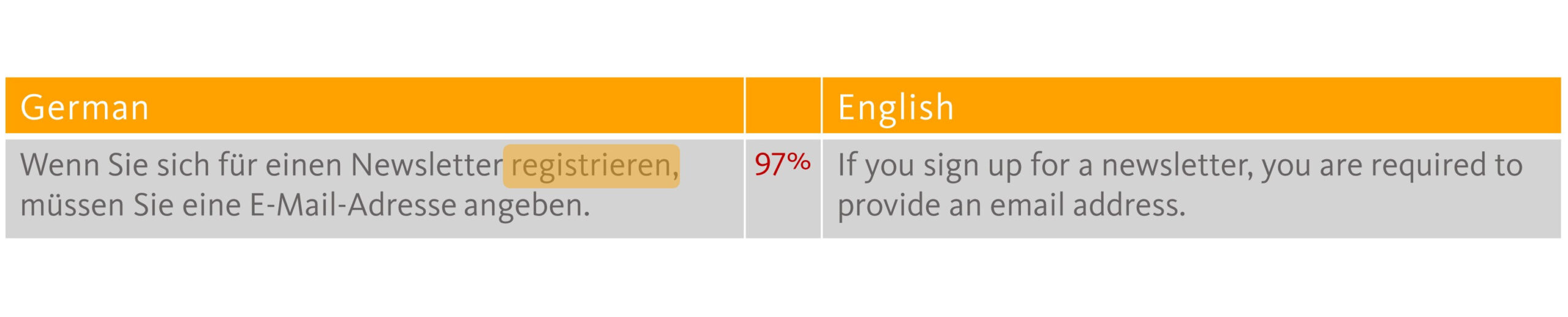

When a terminology database is integrated into the translation project in the CAT tool, all recognised source language terms are marked and (if present) the target language terms from the database are displayed directly.

What does this have to do with translation-oriented writing?

You would be right to expect a service provider to display expertise in translation technology and the way in which TMs and terminology databases work. Nevertheless, authors of technical texts should also be aware of the pitfalls related to translation technology that may be hidden in their content and eliminate them.

Layout issues

In terms of using translation technology, one of the main reasons why texts are often not suitable for translation is formatting. Who hasn’t seen it? The author prefers to move a word over to the next line, to indent text differently or to hyphenate a word differently in order to make optimum use of the space available in the layout. So we quickly try to fix it.

However, manual intervention in the layout can be problematic, particularly for segmentation, but also for terminology recognition. Instead, as the following examples show, the formatting tools available in text editors should always be used.

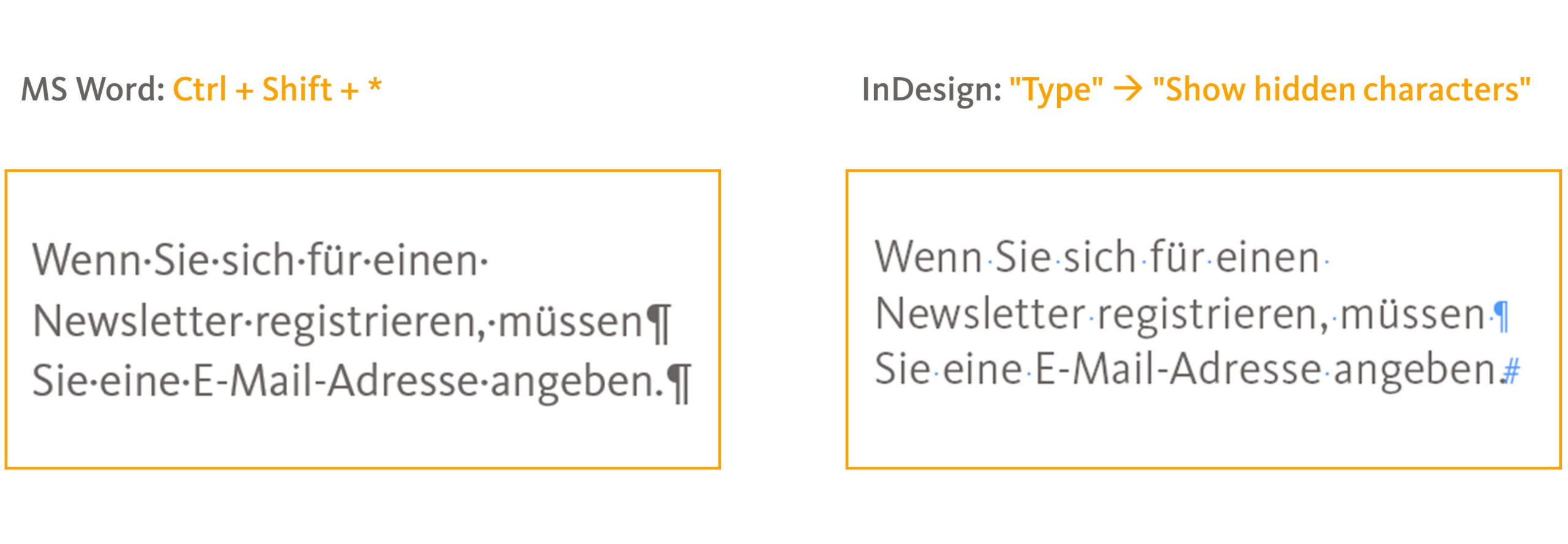

In principle, it makes sense to show the paragraph marks/bookmarks in all text editors. (This is possible with MS Word and Adobe InDesign, but unfortunately not with MS PowerPoint or MS Excel.) This allows you to see superfluous interventions in the formatting directly:

Show paragraph bookmarks – Recommendation

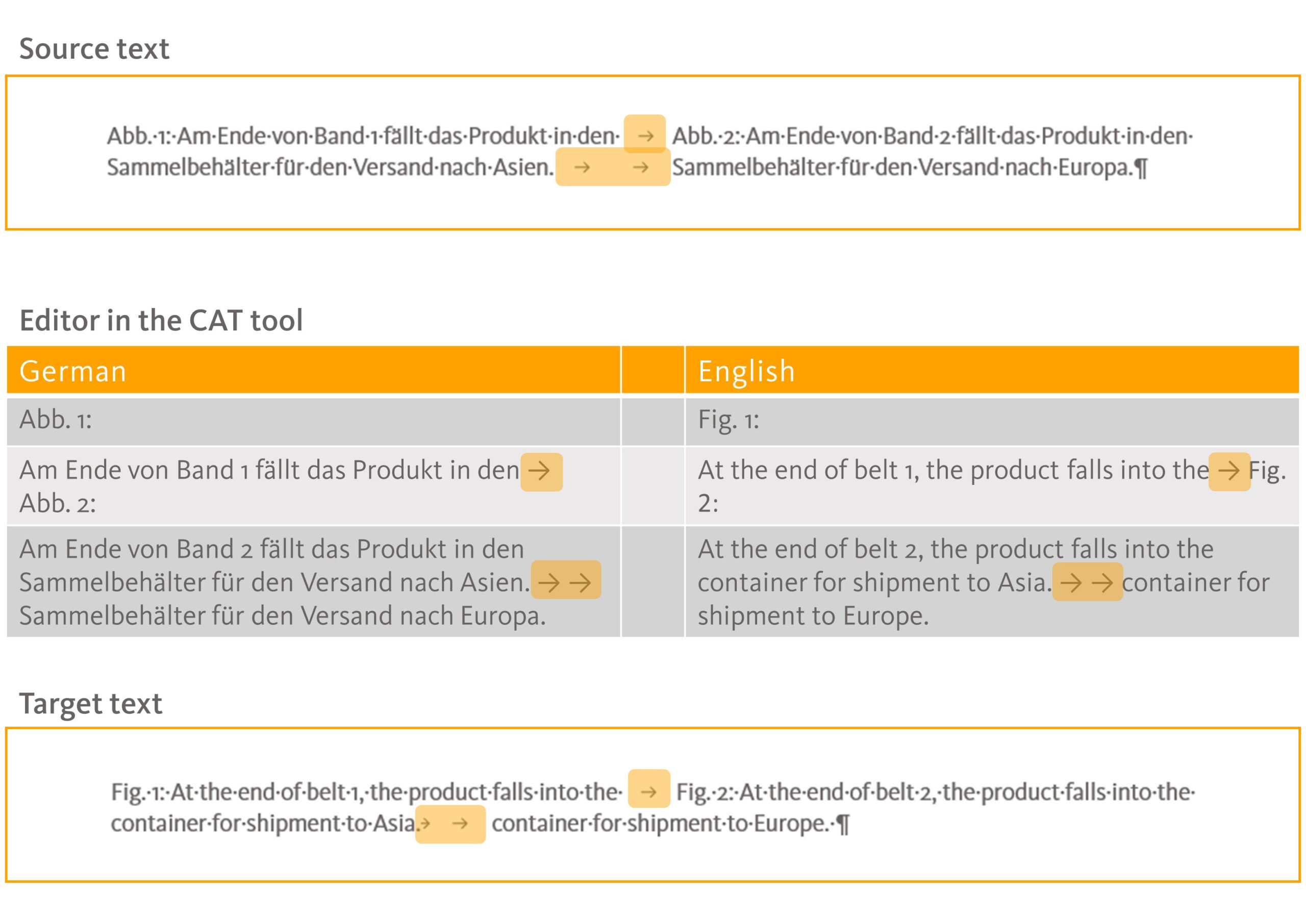

Scenario 1: Manually forced line breaks

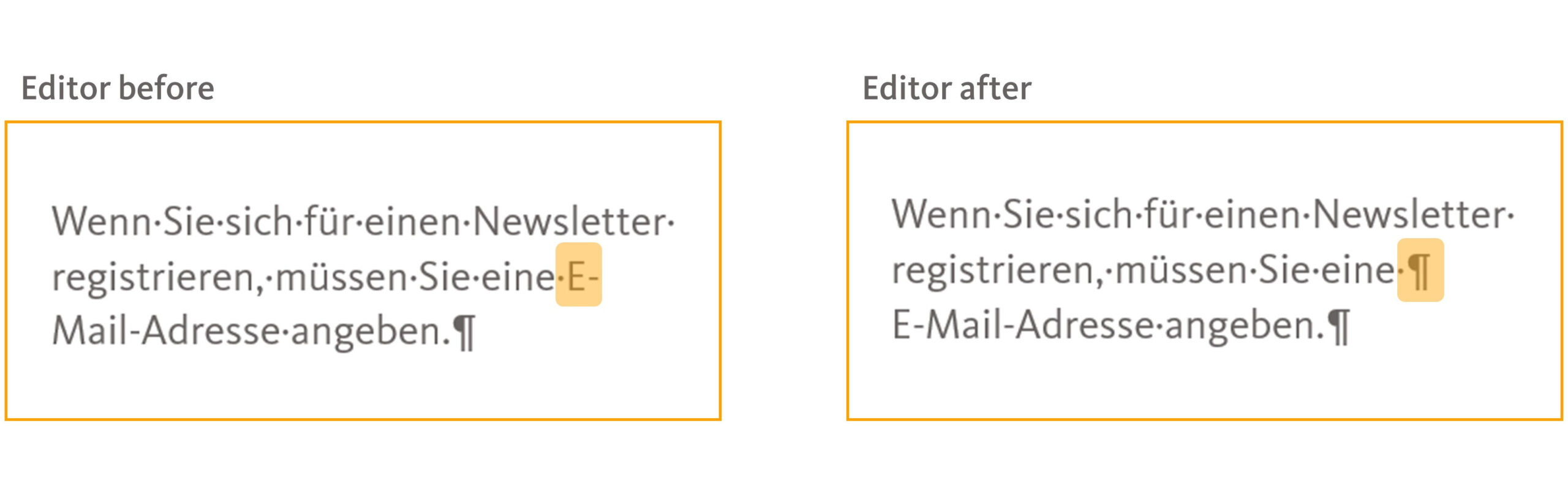

Hard returns (Enter, ¶) are regarded as stop marks for segmentation. So if you insert a hard return in the middle of a sentence for layout purposes, a single sentence becomes two segments. This can lead to additional work in file preparation in order to delete the breaks in advance or to merge separated segments in the CAT tool. However, if it isn’t rectified, two or more segments are created. It becomes much harder to meaningfully translate them and they may be unusable in other projects.

Hard returns in the text editor

Hard returns – effects in the editor in the CAT tool

Hard, manually inserted returns should therefore be avoided at all costs. Alternatively, soft returns (↵) can be used, which fulfil the same purpose but are not treated as stop marks. However, just as with hard returns, it should be noted here that the return may be in a completely different position depending on the length of the translation and may therefore no longer fulfil its purpose for layout design.

The use of a protected space (°) can also prevent parts of text that should not be separated from being segmented. It is therefore recommended for use with abbreviations such as “z.°B.” (zum Beispiel, “for example”).

Protected hyphens (-) also help to avoid unnecessary text fragments and segmentation. If, for example, the hyphen in “e-mail” is replaced by a protected hyphen, this prevents only “e-” from appearing at the end of one line and “mail” at the beginning of the next.

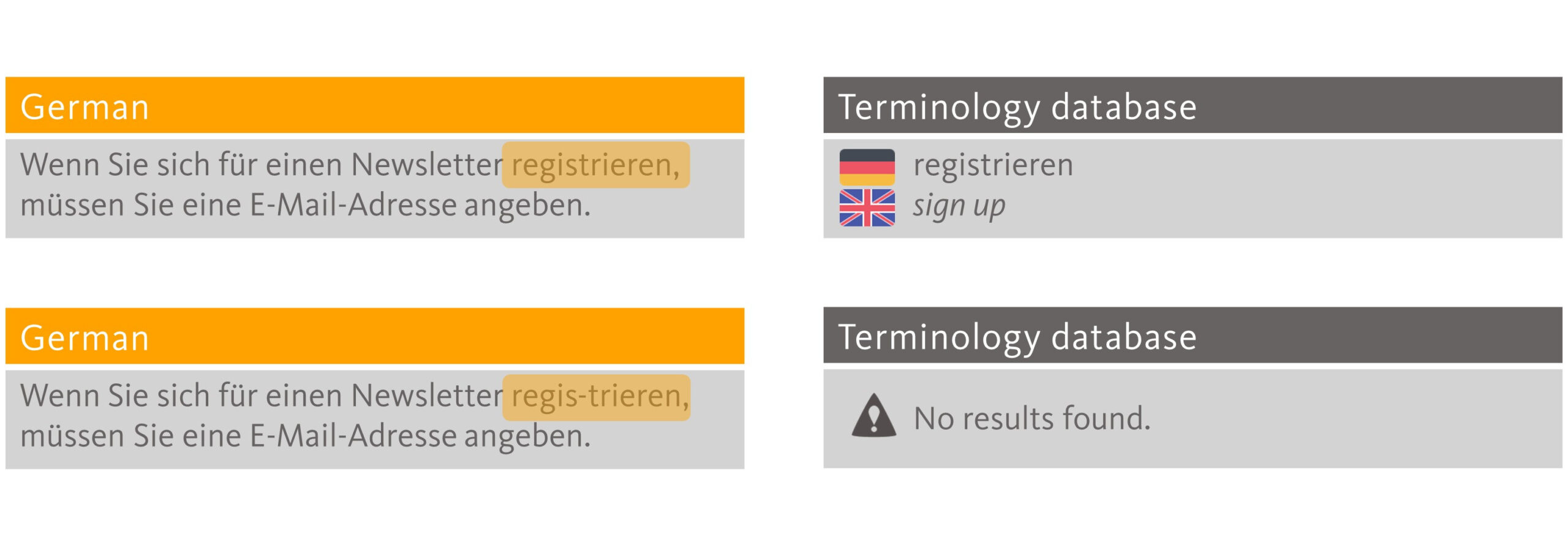

Scenario 2: Manual hyphenation

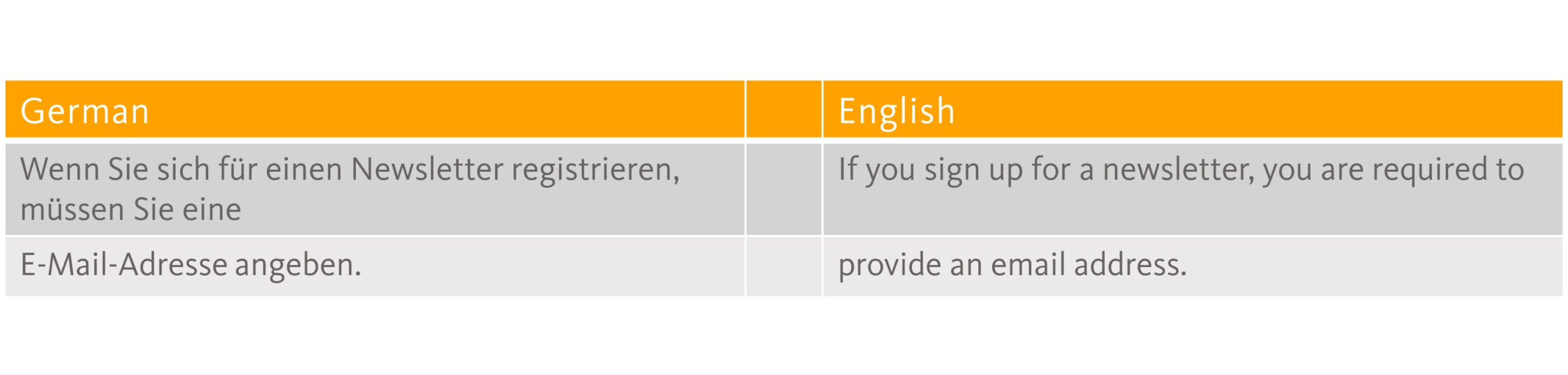

While protected hyphens affect words that always contain a hyphen and must not be separated at these points, hyphens are also used to manually split words to optimise layout. This prevents long words from being fully moved onto a new line, avoiding large gaps in the text. As this is a manual intervention and not a system-related character, the hyphen also appears as a character in the source text. If the layout changes in the future, the character must also be removed manually, which may lead to lower hit rates and thus additional costs during translation.

Hyphenation

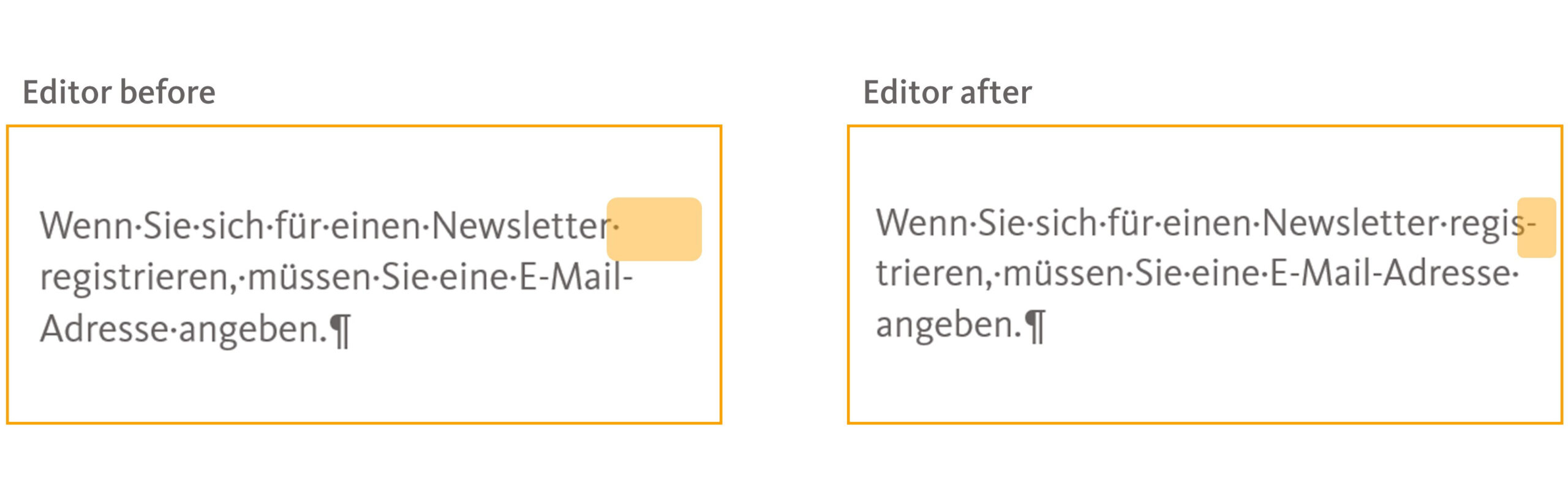

Hyphenation – effects in the editor in the CAT tool

Hyphenation – effects for subsequent projects

Terminology recognition can also be impaired by the addition of hyphens. For example, if the word “register” is stored in the termbase, the word “reg-ister” would not be recognised. There is therefore a risk of inconsistent and incorrect use of terminology. We would therefore always advise using the automatic hyphenation function of the text editor.

Hyphenation – effects on terminology recognition in the CAT tool

Scenario 3: Manual indentation using tabs and spaces

In addition to hyphens and returns, tabs (?) or spaces (·) are also used to indent text or parts of sentences to optimise the layout. Here too, the layout for one language cannot be automatically transferred to other languages due to the different lengths of the translations. In the worst case scenario, manual interventions such as additional indentations interrupt the text flow in the translation and make manual rework necessary. Revising the source text and retranslating it may also result in additional costs – as in the example above – because changed tabs are treated as changed source text and segments are translated again even if a translation for them already exists. The solution in this case is to again work with the formatting functions of the text editor, for example with indents, column sizes and margins.

Tabs

Terminology issues

Terminology and different spellings can also be a reason why texts are not suitable for translation (with regard to the use of translation technology). To optimise flow for reading, it’s easy to be tempted to not always write out specialist terminology in full. Terms and abbreviations commonly used internally also appear in writing without the author explaining what they mean.

The following examples show why failure to be attentive to word choice can be problematic, especially for terminology recognition, but also for machine translation systems and human translators.

Short forms and abbreviations

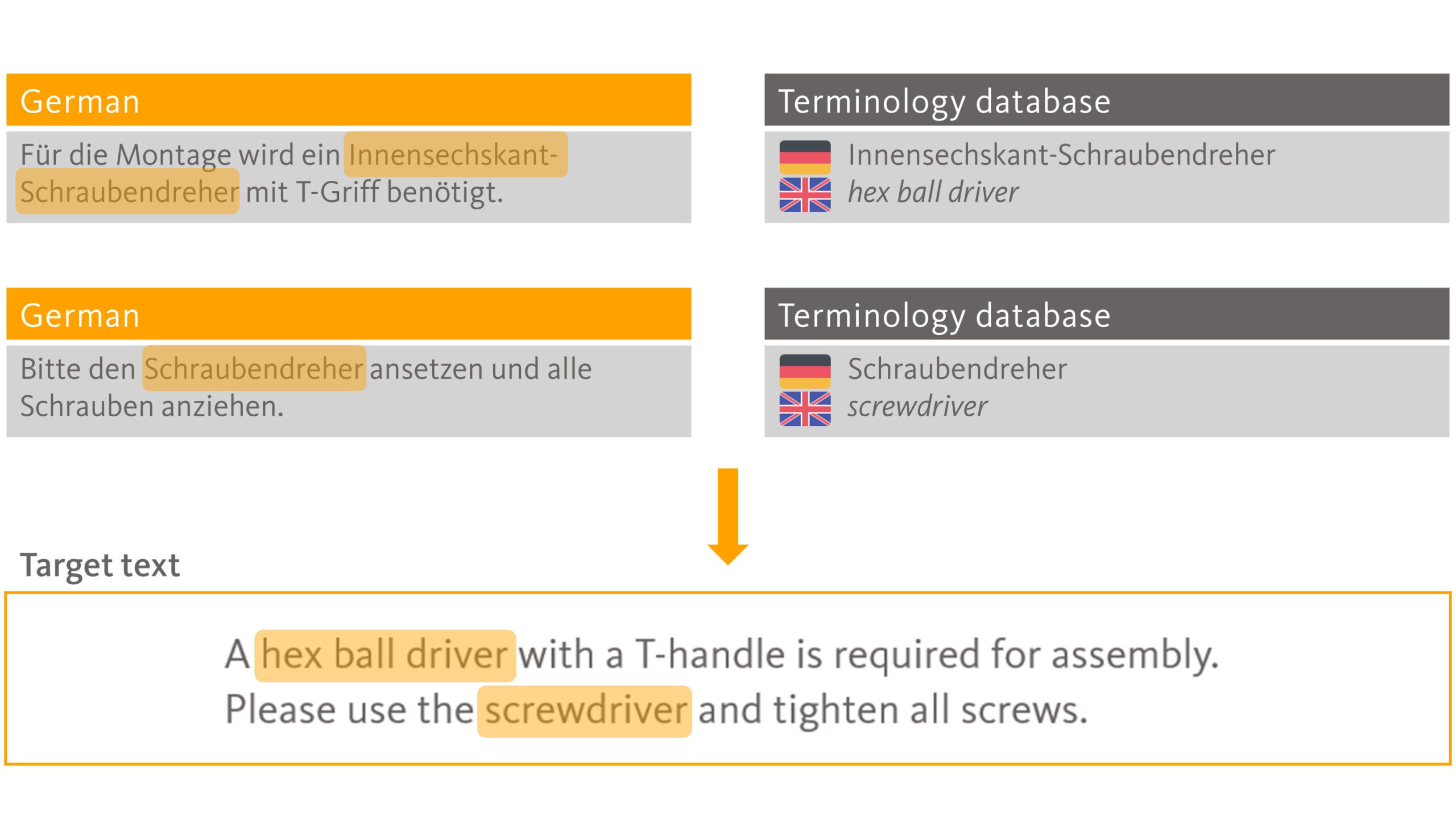

In the first example, the long form (Innensechskant-Schraubendreher) is used in the first sentence, but then only the short form (Schraubendreher) is used. However, the English equivalents according to the database differ so it is not clear to readers that the text is talking about the same tool.

Short forms

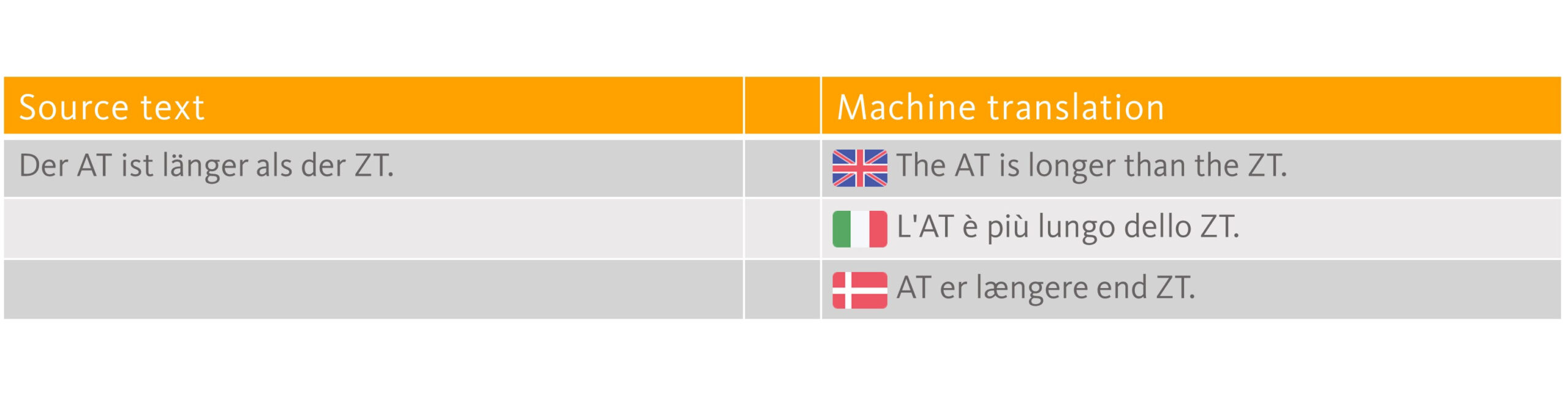

Unfamiliar or unusual abbreviations, such as ST and TT for source text and target text, also complicate translatability and lead to queries. Machine translation systems, in turn, often simply copy abbreviations from source text to target text, which is a frequent source of error.

Abbreviations

Even if text modules are exported from CMS systems, they often lack context and the text section to be translated may only contain short forms or abbreviations. This quickly leads to inconsistencies with previously translated text passages. As a solution, we recommend using technical terms in the long form and explaining abbreviations in a list of abbreviations.

Synonyms

There are at least two reasons why authors use different terms for the same concept: either they want to make the text more relaxed and more interesting by introducing variety, or no standardised terminology has been defined, so there is no specified term to use. The result is multiple technical terms (e.g. the German terms Schraubenzieher and Schraubendreher, which are both translated as screwdriver) and therefore the potential for uncertainty among translators and readers as to whether they refer to the same thing. This proliferation can only be avoided by always using the defined terminology, regardless of how often a term is repeated in the text.

Conclusion: a little effort will deliver good results

Even a few simple optimisations can improve source language content, which also benefits readers and users working with the original text. It also minimises translation errors, additional work, lost time and unnecessary queries. Key factors for success include the use of the formatting tools available in text editors and as little manual intervention as possible in formatting and layout, as well as the consistent use of specified specialist terminology.

Would you like to find out more about translation-oriented writing when using CAT tools? Then contact the author and expert directly by dropping an e-mail to e.tillmann@oneword.de.

8 good reasons to choose oneword.

Learn more about what we do and what sets us apart from traditional translation agencies.

We explain 8 good reasons and more to choose oneword for a successful partnership.